Read Part I here.

“Do you have your strategy?” asked Luca’s therapist as he pulled Luca’s and my canoe into the lake.

Strategy? I asked myself, as I stuck my oar haphazardly in the water.

It was Day 3 of the workshop. The therapists had created a Family Olympics in which families competed in different games designed to foster unity and communication. This game was a canoe race, and we were told to canoe around a series of buoys as fast as possible.

Apparently, we were also supposed to come up with a strategy before heading into the water instead of just winging it — my usual approach to athletic endeavors. Our “strategy” consisted of Luca sitting in the back of the canoe, yelling instructions, and me, trying to coordinate my tentative paddling with his while hoping we didn’t fall in.

I would be reminded the next day when we listened to the lecture on learning disabilities, that my ability to think in spatial terms is practically non-existent. So when Luca told me to let him do the steering and to just paddle as hard and I could, I didn’t conceptualize what he was saying, or listen.

Part of the reason I didn’t really listen is that Luca gives directions incessantly, whether or not you ask for them. So I tend to zone out when he embarks on one of his lectures.

Another reason I didn’t listen is because I hate doing anything athletic in front of others, unless it’s yoga or Pilates or jogging, none of which I consider athletic. The canoe race brought back stomach-lurching memories of coming in last during school relay races, or standing in the middle of the soccer field praying the ball wouldn’t come towards me so I’d have to kick it.

My “strategy” during athletic competitions is just to get through them any way I can. I was rattled by Luca’s yelling from the back of the canoe and I couldn’t remember which buoys we were supposed to paddle around, so we came in second to last, just ahead of the frustrated boy whose mother and sister were wearing full make-up and work-out pants with THINK PINK emblazoned across the butt.

“Mom, you didn’t paddle hard enough!” Luca repeated several times — loudly — in front of people, as we stepped out of the canoe and back onto the ground.

“Would you please stop yelling at me?” I snapped.

So much for unity and communication.

* * *

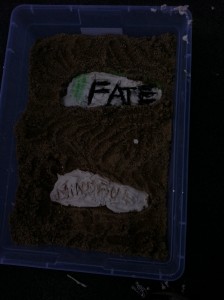

The next exercise involved tactile sensations, crafts, and words, so I was in my element. Teamed with our children, we were told to step one foot into a tub of damp sand, then pour plaster into the footprint mold. After we’d sprinkled colored granules onto the footprint, we used sticks to write a word in the drying plaster that described a lesson we learned, or an intention we wanted to set, or a feeling. The goal of the exercise was to help family members get closer by learning what was important to each other.

“Sometimes families write words that are in opposition to each other,” explained the therapist, “like ‘freedom’ and ‘structure.’ And some families write words that have similar themes, and you find out you’re more in sync than you thought.”

I stared at our footprints. Luca had written “FATE” on his and I had written “MINDFUL” on mine.

I felt sadness tug at me when I saw Luca’s word. I assumed that he believed the course of his life was fated, and that he had no control over anything that happened to him.

But that wasn’t the case when the therapist asked why he chose the word.

“You make your own fate,” he explained. “If I hadn’t made bad choices, I would still be at home, but because I made bad choices I got sent to wilderness camp, and then here. So I can control my destiny if I make better choices.”

The therapist nodded.

“We all can, right? And if we think we’re going to succeed, we’ll probably succeed.”

I let Luca’s explanation sink in. I had no idea he had started to see the connection between his actions and being sent to residential, that he was beginning to shift from blame to accountability.

“I wrote ‘mindful,'” I said. “Because I spend too much time regretting things I could have done differently, or worrying about the future. I’d like to learn to practice mindfulness, so I stop missing out on what’s going on in the present.”

“So your words work together,” said the therapist. “If you’re mindful, you have a better chance of controlling your fate.”

I nodded. The fact that Luca and I were on the same growth curve struck me as incredibly profound. I looked over at him, wondering if he felt the same closeness.

He stifled a yawn.

“Can I fly my helicopter now?”

* * *

When the workshop was over, we drove from the camp site back to Luca’s school. We passed rapids…

…and miles of mountain ranges.

Luca wanted pizza, so we pulled into a tiny, one-road town and stopped at a pizza joint that had wi-fi. We had been unplugged for three days and Luca asked to download a free game on my iPad.

During Luca’s last home visit, I kept my computer password-protected and told him he could only use his laptop. I didn’t want him to discover any trace of Pauline Gaines, for many reasons, but mostly because I didn’t want him to feel exposed or exploited.

Although I have purposefully changed names and locales and have cropped faces out of every photo, I don’t know what meaning Luca would make out of his part in this blog. Some day I may show him the blog and ask him if I could write a book about what our family has gone through, using our real names. But only when he’s old enough to have gotten some distance from these years, and only if he gives his blessing.

I looked down at my iPad. Was it safe to give it to him? I knew I was logged into my “real me” Facebook account. Luca had, for the most part, been cooperative during the workshop and hadn’t grumbled about having to camp instead of stay in a hotel. So I wanted to reward him.

“You can download the game,” I said. I thought of telling him not to go anywhere else besides the game apps, but I was distracted checking my e-mail messages on my iPhone. I had received several, progressively urgent e-mails from my HuffPost editor asking for revisions on a piece I’d forgotten I’d submitted.

When I glanced up at Luca, I saw him staring at the iPad screen, a puzzled look on his face.

“Mom, your Facebook is weird…”

My stomach traveled up to my throat. I reached across the table and tilted the iPad screen towards me. I saw both my Facebook account images on the screen: the real me, with my photo, and “Pauline Gaines” under a silhouette.

“I logged you out, I wanted to check my account…” he said.

“You need to stay off of Facebook,” I said, trying to act as if it was perfectly normal to have a Facebook alias. “You can use the iPad to play the game when we get back in the car, and that’s it.”

I put the iPad in my lap. The pizza came. I tried to still my racing mind: He’s not allowed to use the computer at school… by the time he can access a computer, he’ll have forgotten the name….maybe he’ll have forgotten he ever saw it.

Maybe I need to start being mindful.

* * *

The rest of the drive back to school was different from the drive up just three days before. The stiltedness was gone. There was more, and easier, talk, and more laughter. We stopped at a scenic overlook to take pictures and Luca used the reverse button on my iPhone camera to snap a photo of us.

Luca navigated us back to school. I noticed how he greeted a kid — the same kid who had exploded the first day of the workshop, who was too angry to come on the camping trip — in a friendly manner and told me how “funny” he was.

This type of sociability is new for Luca, who historically has held kids he perceives as different at a disdainful distance. Despite his protests that he “hates” kids at his school during family therapy phone sessions, his actions during the workshop suggested the opposite. He seemed to enjoy being part of a group, and being accepted.

After we dropped off his bags with Staff, Luca walked me to my car. We hugged and he promised to write me letters from the regular sleepaway camp that he has gone to since he was ten, and where he was heading the next day. He had reached a high enough level at school that he was rewarded by a two-week stint at camp, where he will spend most of the time playing paintball.

I drove to the airport, returned my rental car, and headed to the ticketing area. No one was there, which I thought was odd. Then an “oh no” feeling seized me and I reached into my purse, frantically, and pulled out my flight itinerary. The 9:00 p.m. departure time was actually for my connecting flight. I had missed the first departure by a half hour.

If you’re mindful, you have a better chance of controlling your fate.

I hauled my grimy self (the camp site had no showers) to an airport hotel, scheduled a flight for 8:00 a.m. the next day, and collapsed on the bed, falling asleep to a Law & Order SVU rerun.

When I awoke at 5:45, I showered and packed my things, wrapping Luca’s plaster “FATE” footprint in clothes and slipping it carefully into my carry-on backpack. I placed my “MINDFUL” footprint in a plastic bag and packed it as well.

This time, I arrived early at the airport. I sat at a table outside a coffee shop, drinking a smoothie and reading my iBook.

“Mom?”

I looked up to see a grinning Luca next to a burly Staff.

“Did you miss your flight?” as in, that is so typical of you.

Luca was at the airport to catch the flight to his summer camp. I told the Staff I would take him to the gate. We checked his bags, with Luca still shaking his head in amusement.

I bought him a bagel and an Arizona tea at a food kiosk. As we were waiting for the bagel to be toasted, I realized how wonderfully mundane it felt to buy my kid some breakfast and make sure he got on his flight: tasks that I’d missed the past few years of his life.

We hugged at the gate, and I wrapped my arms around his bony shoulder blades.

“Love you, Mom,” he said.

“Love you too. Have a great time.”

He walked down the aisle to board the plane, turning back towards me as if he’d read my mind.

“I’ll write you!”

I smiled and waved at him, then watched him round the corner towards the plane.

* * *

I unpacked when I got home, holding my breath when I drew Luca’s footprint out of my backpack. It was in one piece. I searched for my own, my hand rooting through the different pockets of the backpack.

Oh no…

I found it in the front pouch of my suitcase. The suitcase that had buffeted its way into and out of the baggage hold. The plaster footprint had cracked into several pieces inside the plastic bag. I vaguely remembered the night before, thinking I need to place it in my carry-on backpack, next to Luca’s. Obviously, I’d been my usual mind-racing self, and hadn’t.

When you’re mindful, you have a better chance of controlling your fate.

Clearly I have a lot more work to do on being mindful. But maybe Luca’s exodus out of our home and into wilderness, then boarding school, has taught him that his fate is in large part determined by his actions.

As I collected the shards of my now ironically-named “MINDFUL” footprint and put them on a plate, I thought again about Appointment in Samarra. I thought about the unresolved mishigas from both my and Prince’s childhoods, the careless, immature way we’d related to each other so often during our marriage, and how our lack of mindfulness created a terrible fate for Luca.

I thought about Luca’s succession of impulsive choices. They led him away from home, but to a new home where I think, I hope, he has been rebooted. And maybe, if what he has learned sticks, Death will go looking for someone else in Samarra.

Love hearing about your family – esp good news

Terrific post. A promising story on a road to recovery and healing. I feel for you in enduring your son’s absence. I have a long distance relationship with mine and it’s extremely hard. It’s the mundane that we miss. The grumpy breakfasts, the goodnight hug or the silent drives to the footba field…

Great post, Pauline. If you think Luca is going to forget your Facebook profile, you are not being mindful. Kids love mysteries. LOL Have a great weekend!

Sigh. Please just let me dwell in my wishful thinking awhile longer.

They’re sponges (with all the pros and cons that means); they’re all too observant (more pros and cons); they also understand more than we think, at least, it’s what I believe – and have found to be true over the years with my own sons.

It sounds like so much healing in process, and also, maturing.

Don’t worry about Facebook. There’s nothing to be done, now. In my experience, kids don’t pay any attention to what I’m writing or doing, and I try not to pay them much attention either.